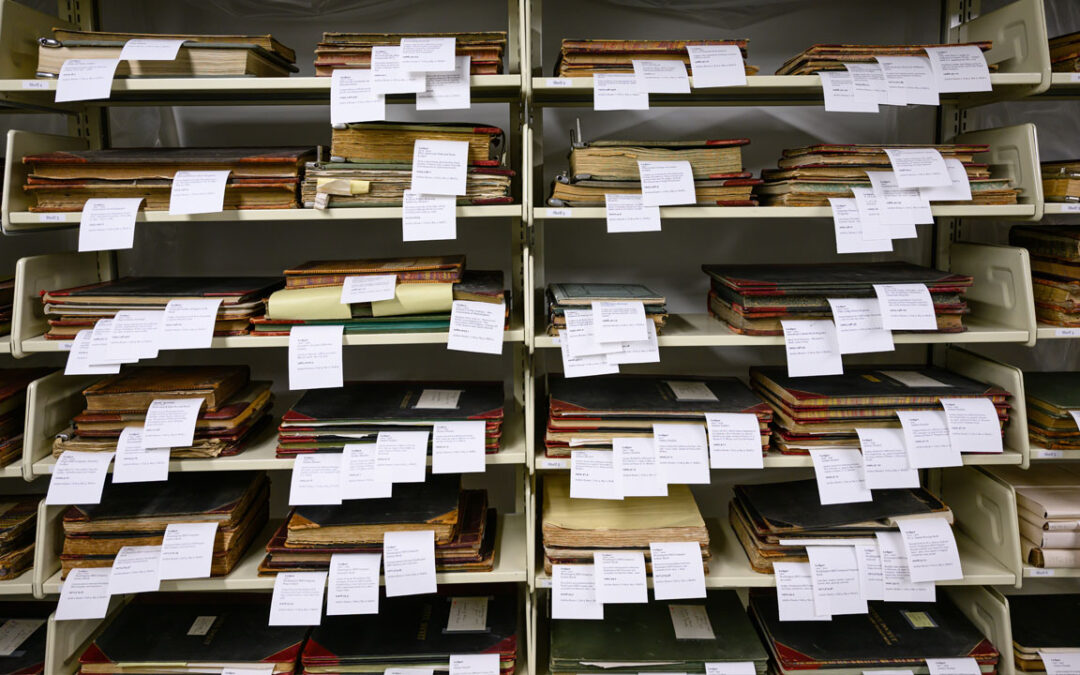

You may have heard us say it before: Our collection is home to roughly 500,000 items. That’s a lot for an organization of our size and only a fraction of a percent can be displayed at one time. While caring for those items is some of the least publicly visible work we do, it’s essential. It’s one of the big reasons communities contribute items with historic or cultural significance to museums like ours, rather than warehousing them in unstable storage or leaving them exposed to the elements.

The ongoing collections work happening behind the scenes is what ensures items and all the information they hold are well preserved and can be shared with future generations. That matters because archives and objects help us tell the immersive stories that inform, delight, and surprise us. Simply put, collections are foundational to our museum experience. That’s why we have staff dedicated to caring for and facilitating access to the JCHS collection at our Research Center. A full written account of what they do day-to-day could fill a tome. We can’t cover it all at once, but we can share a little at a time—starting with the subject of this collections spotlight: conservation activities!

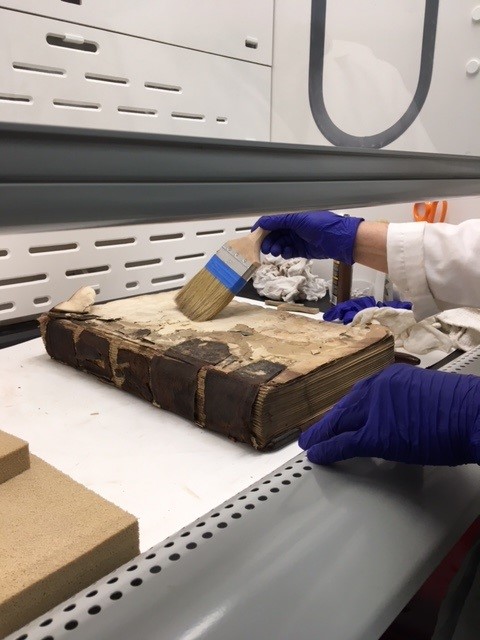

Following the completion of a multi-year, multi-phase renovation at our collections storage facility earlier this year, we are now able to turn our attention to the long-term stabilization of artifacts. Why is this something we need to actively do? Because if we don’t, objects deteriorate as a natural result of time, storage conditions, the presence of pests, wear and tear, or some combination of these factors. For us, this dedicated conservation effort means that over the next two years, our collections team will clean and treat hundreds of objects in our collection. Many of these items have been impacted by mold, which likes to feed on items made of paper, fabric, leather, wood, and other organic materials. For items that have suffered mold growth, the treatment process requires removing mold and deactivating spores that remain to reduce the likelihood of future problems.

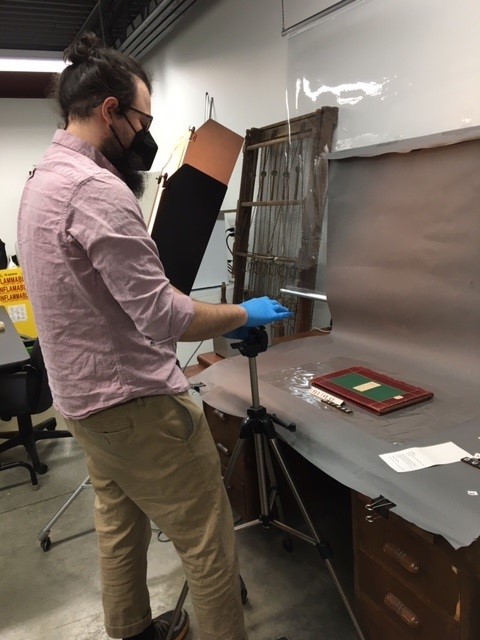

Leading the charge for this conservation project is the marvelous Laura Reutter, an object conservator (and talented artist in her own right!) who has worked with JCHS in many capacities through the years. Helping Laura with this project is our also-marvelous Research and Collections Coordinator Reed Barry.

Here are the broad strokes of their process: Before an object is cleaned and treated, Reed photographs it and makes detailed notes of its condition at the time it’s moved from storage. This practice of condition reporting can provide a critical reference point—helping us spot changes to the object since the last time it was moved, potential signs of unstable storage conditions, and in some instances, evidence of pests. This is important because one major goal of collections care is maintaining the stability of an object for many years—with thousands of items to care for, it may be decades before staff reviews some of these objects in this much detail again.

After the condition is documented, artifacts move into Laura’s care, where she cleans and treats the surface using soft brushes, absorbent sponges, and solvent solutions. Once cleaned and stabilized to Laura’s satisfaction, the items return to a freshly scrubbed storage unit.

It’s worth noting that conservation needs can vary as widely as the objects in a museum collection. Everything from the material properties, age, alterations made over time, and overall condition help determine treatment needed to stabilize items so they can be handled, stored, transported, accessed, exhibited if needed, and ultimately preserved. Lots of different items are in the scope of this large conservation project, but (as you can hopefully see in the photos) Laura and Reed have started with our collection of antique ledgers.

What can you find in our collection of ledgers? The short answer is lots of stuff! But for this occasion, we’ll highlight that every edition of the Port Townsend Leader dating back to 1889 is among these bound volumes. You may have heard the old saying: “Journalism is the first rough draft of history.” There’s some truth to it—we can learn a lot from the way events were reported as they unfolded, even if the accounts weren’t complete or objective. It’s the reason newspapers are some of the most frequently accessed resources in any museum’s archival holdings, and our editions of the Leader are no exception.

Collections care like the work Laura and Reed are doing is a big part of the responsibility we bear as a repository for incredible community resources. After they work through the ledgers, they will examine artwork, wooden furniture, textiles, and photographs for condition problems. The scope of this two-year conservation project was informed by a collections survey Laura performed for JCHS in 2018. Periodic surveys are standard practice in museum collections, and they help us estimate the extent of remedial treatment needed so we can plan and budget for conservation work like this.

To be clear, conservation projects are not a one-and-done. Taking a systematic, well-documented approach to treating objects is as much for our benefit as it is for future JCHS collections staff, who will have to make collections care decisions partly informed by some of this work we’re doing now—all so the public can continue to access and learn from our collection. Suffice to say, there’s plenty of conservation work ahead and this is just one of many projects our awesome collections team has going.

Resources to start learning more about museum collections and conservation:

- Conservation of the Collection from The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- The Collection Connection, our own video about the magic of collections

- Vacuuming Moldy Books & Paper, an educational video from Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC) with tips for safely removing inactive mold from books and paper

- Museum Conservation, an overview of different types of conservation work from the J. Paul Getty Museum