Did you know you can find many of the photographic images, archival descriptions, and catalog records in our collection online? Our online collection is a vital resource that connects researchers all over the world to items that would otherwise only be accessible at our Research Center in Port Townsend.

You can find thousands of images and records in our online collection, and more are being added all the time. Even so, our online search still represents only a fraction of the roughly 500,000 items in JCHS’s entire collection. So, how do we determine what to add to the online collection and when? Research value, risk to the original items, copyrights, and staff capacity are all factors. Another is the more practical matter of how to capture a physical item in a digital format.

Every image of an item that’s been uploaded to our online collection is the product of digitization—the process of scanning, photographing, or recreating an item with a digital program. If you can imagine the variety of items in our collection—small, large, two- or three-dimensional, fragile, heavy, and sometimes even hazardous to handle—you may also be able to imagine how different the digitization process can look depending on the item. A great case in point is a digitization project that JCHS has been working on for the last several months.

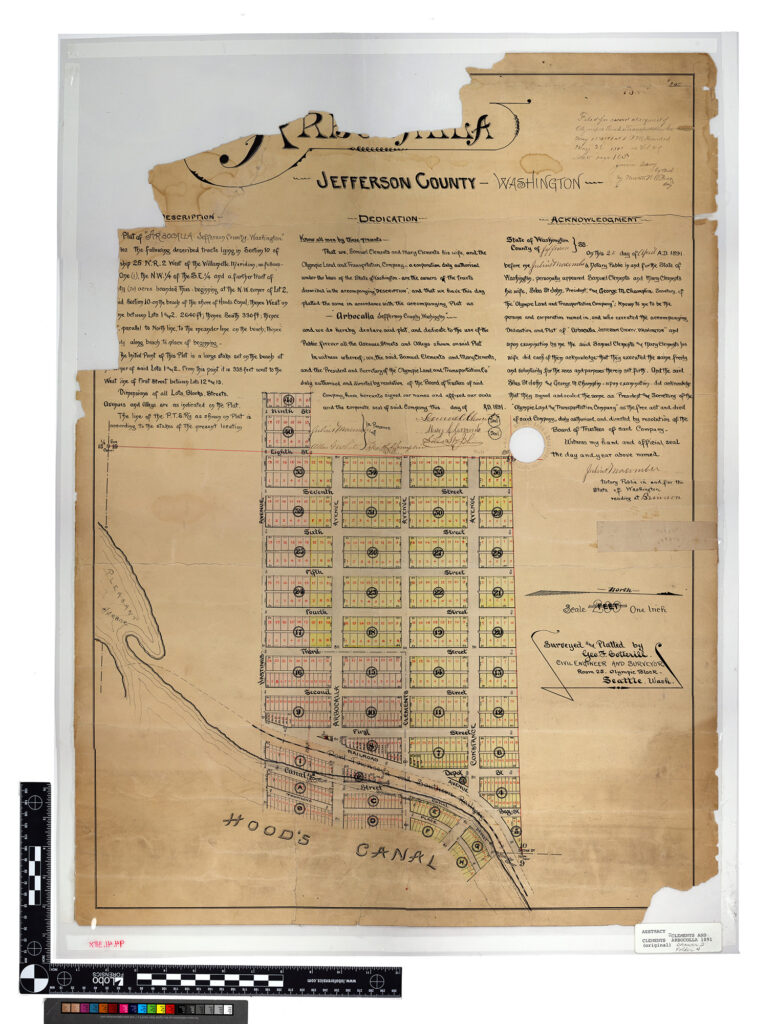

With funding from the Washington Digital Heritage Grant program, our collections team has been working to digitize hundreds of maps as the foundation of our new Maps and Technical Drawings collection. To walk us through the intricacies, benefits, and unique challenges of digitizing items like maps, we called upon our awesome Director of Research and Collections Ellie DiPietro.

Why maps?

Have you ever wondered how items get digitized and put in our online collection or how museums decide what becomes digital? With roughly 500,000 items in our collection, prioritization is of essence, and we zeroed in on maps as the focus of our next big digitization project for many reasons.

For starters, we have a lot of them. JCHS has several hundred items listed as maps, blueprints, technical drawings, or otherwise cryptically labeled “oversize.” Maps in particular are also an incredible resource for historical information on a specific location, often containing useful insight into patterns of land use over time. So, our maps are great in terms of volume and research value. Their condition, however, has presented some challenges.

Many of the maps in our collection have been restricted for years because they are old and decrepit—some literally crumbling to dust when we touch them or pull them out for research. As an added layer of complication, the written summaries describing some of these maps (what we call “finding aids” in museumspeak) have generally not been robust enough to identify which ones are useful for research requests. To say the least, having a number of under-described maps with potentially vital historical information that may or may not be in delicate condition is not ideal.

Fortunately, digitization can remedy many of these challenges around preservation and access. So, around this time last year, we started strategizing a method to digitize as many maps and oversize materials as possible, as efficiently as possible. Ultimately, the project we mapped out 😉 was awarded grant funding in June 2022.

Now—over 200 hours, 4,000 images, and 400 GB of data later—we have 500-600 unique items destined for upload to our online collection by the end of May 2023. Roughly 400 of these newly digitized items are maps and you can find the results of all this work in the new Maps and Technical Drawings collection.

Introducing the Digitistation

So, what was this so-called “efficient” process we cooked up? Imagine someone taping together several sheets of 8.5×11 copy paper to create a larger sheet. What we did was similar! We photographed each of our oversized items as a series of smaller pictures, using a setup dialed in to have smooth lighting, a consistent camera placement, and a shuttle to touch the item as little as possible. We also developed some small calibration dots to help with aligning and stitching the photos together.

Performing most of the yeoman’s work of this digitization project once we’d perfected our method was our Research and Collections Coordinator Reed Barry (who you may remember from this previous story about collections care). As staunch lovers of puns and clever portmanteaus, we couldn’t resist dubbing this setup the Digitistation.

Our station ensured that our brittle maps had no excuse but to show their best side. The consistency and calibration assistance enabled the computer to do most of the heavy lifting for us. One object at a time, we combined smaller images into composite images using Adobe Photoshop’s automated Photomerge stitching function.

About 80% of the time, Photomerge’s stitching works with little error so our staff can move on to the peskier maps. The other 20% of the time, the stitching creates more avant-garde distortions that would confuse the mightiest of cartographers. For composite images that don’t come together easily, we’ve had to merge images manually, making stitching the largest hurdle to ultimately getting all the images online. Below is a comparison of a composite image that comes out as planned and one with a more, um, bewildering outcome.

Right: Landscape planting plan of Point Hudson (Object ID 1994.42.6x). A truly unique arrangement if Photoshop’s AI had the final say.

We’ve prepared the images of these maps to be a representation (not perfect duplication) of the original object. And, I must say, they look GREAT! The online version has been reduced in size to a maximum dimension of 4,500 pixels on the longest edge. Images larger than this load slowly, and this resolution is high enough to read even the texture in the paper on most of these maps.

The resulting composite images may display some minor misalignment, skewing, and/or distortion, because after all, Photomerge is an AI technology, and computers are not ready to take over from their human overlords! Nonetheless, if you see something that is unclear in the online collection, there are many images in our digital storage that will have better clarity and the originals are being cared for in a paradise of cool and dark storage where no one touches them. If you ever need or want a closer look of something you find in our online collection, consider planning a visit to our Research Center for some assistance from our knowledgeable staff and volunteers.

As people who work with historical materials every day, our collections team is thrilled to have an easy way to share these maps without risk of damaging one-of-a-kind materials in our collection. While digitization ensures greatly expanded access to these maps, careful storage is what preserves them so future researchers can see them in closer detail if needed. Both are essential aspects of collections stewardship and our own mission.

We couldn’t undertake projects like this without the support of our community and funding from sources like Washington State Library’s Washington Digital Heritage Grant program. We hope you’ll check out some of the results of this project and explore our larger online collection.

If you want to learn more about our hundreds of newly digitized maps, don’t miss our upcoming Research Center Open House! Join our research and collections staff Saturday, June 24 from 1:00 to 4:00 PM for a free behind-the-scenes tour of special collections, hands-on activities, and a chance to ask our team your questions about collections care.

This project is made possible by the Office of the Secretary of State through the Washington State Library and the Institute of Museum and Library Services. Use the search term “WA SOS”, “IMLS” or “WSL” in the online collection to see items digitized through this grant.