If you’ve ever accessed our archives for some research of your own, taken a tour with our staff, or browsed our online collection, you know that JCHS’s collection is vast—its contents are varied, much of it cannot be easily digitized for online access, and only a fraction can be displayed at one time. Nonetheless, there’s constant work to be done with it all behind the scenes.

Besides preserving items, there is lots of active care and tracking that goes into collections stewardship. Staff expertise is a big part of it. Our team makes daily decisions to promote the long-term preservation of so many different things, and their familiarity with our collection is essential to the process. Also essential to this work is having the right supplies.

To walk us through some of the challenges we encounter and choices we make around ordering collections supplies, we have called upon our resident expert on the subject—our Director of Research and Collections Ellie DiPietro. Enjoy this deep dive on “the whys of supplies” and learn how you can support collections care this August with a gift to our summer supplies fundraiser.

Museum supplies are complicated

Museum collections are full of many types of materials—paper, silk, cotton, linen, plastic (good and bad), wood, metal, ivory, glass, ceramics, rocks, shells, taxidermy, art, and combinations of all sorts of things!

We manage the risks specific to each artifact with what’s called a care strategy. A helpful analogy is kitchen food storage: Some foods will spoil unless you keep them in a fridge. Some need to be secured because they’re easily broken and damaged (or just appealing to pests!). Others are shelf-stable for a long time and require very little care. But, unlike foodstuffs that stay edible for a short while, we are responsible for trying to keep these objects around for hundreds of years. The care strategy is how we do that.

Building a care strategy

To preserve the various materials in a museum collection, we need to first understand what makes them break down. These challenges to an object’s long-term preservation are known as the AGENTS OF DETERIORATION (cue ominous light-flickers and villainous music).

Depending on the object, there can be many agents of deterioration, but here are some common examples:

- Pests (insects, rodents)

- Light

- Physical force

- Poor environment (improper temperature and/or humidity)

- Water or fire damage

- Thieves

- Pollutants (from the outside or the object itself)

- Custodial neglect (bad paperwork)

We could devote an entire post to these menacing agents of deterioration, but to keep the focus on the importance of supplies, I’ll just highlight my personal favorites—inherent vice and physical force. Inherent vice is the tendency for a material to break down because it is old and physical force includes things like moving objects and handling them for research or exhibition.

Heading off these agents of deterioration is where storage, or what we call housing, comes into play. To determine the appropriate kind, we need to understand what material/s the artifacts are made of, how those materials will change with time, the best way to allow them to age gracefully and stay protected if they are moved frequently, and how we can ensure they shine brightest when on exhibition.

Each year, our collections team makes a list of priorities for the following year with three components:

- Items that have just been added to the collection and need their first housing

- Items that need their housing changed

- Our best guess of what new things might be donated over the next year

After making our list, we then try to choose materials that solve as many of these challenges as possible within our annual budget. Shipping can be as much as 25% of the cost of getting these special supplies, so ordering once a year is the most cost-effective.

When “archival” materials aren’t suitable for the archive

In general, we choose materials that are inert and acid-free. Because acid is great at breaking things down, it can do a number on even the most durable of artifacts. However, not all materials marketed as “archival” or even “acid-free” are suitable for museum housing because they can still contain lignin—the part of tree pulp that becomes acidic with time. Something may be acid-free today that won’t be in 20 years!

After we select supplies that are acid- and lignin-free, we ask three questions for each artifact:

- Does it need to be PAT-passed (ISO 18916)?

- Should it be buffered or unbuffered?

- Is the housing hygroscopic or hydrophobic?

Now, that’s some serious museumspeak that we don’t expect everyone reading to understand, but these questions dictate the materials we ultimately choose, so let’s break them down.

PAT

PAT stands for Photographic Activity Test. Photographs are made from very sensitive chemicals—either metals that tarnish or chemical dyes that break down. Photographs are the most needy and delicate thing in our collection, and we choose materials gentle enough to keep them safe. Anything that might house a photograph or something like a scrapbook will need PAT-passed materials.

Buffering ⏳

One of my go-to millennial-museum-worker jokes is to start singing “every day I’m buffering” (a la Rick Ross’s “Hustlin’”) when working with the collection. In this context, I’m not talking about a slow-loading video. For collections, buffering means using a material with a calcium carbonate layer that balances the pH of acidic materials. We use buffered materials to prevent the build-up of acids in materials that become more acidic with time and can damage themselves by doing so (i.e., most plant-based materials). The most common artifact of this type is paper.

Our archival materials in particular need buffered materials to help slow the process of acid migration and yellowing. At the same time, certain materials like blueprints, which seem like they should have buffering, do not want it. Same goes for animal-based materials, which need their acidity to last long-term. Leather and silk are good examples—changing their acidity will increase their deterioration rate. Even some photographs prefer unbuffered material.

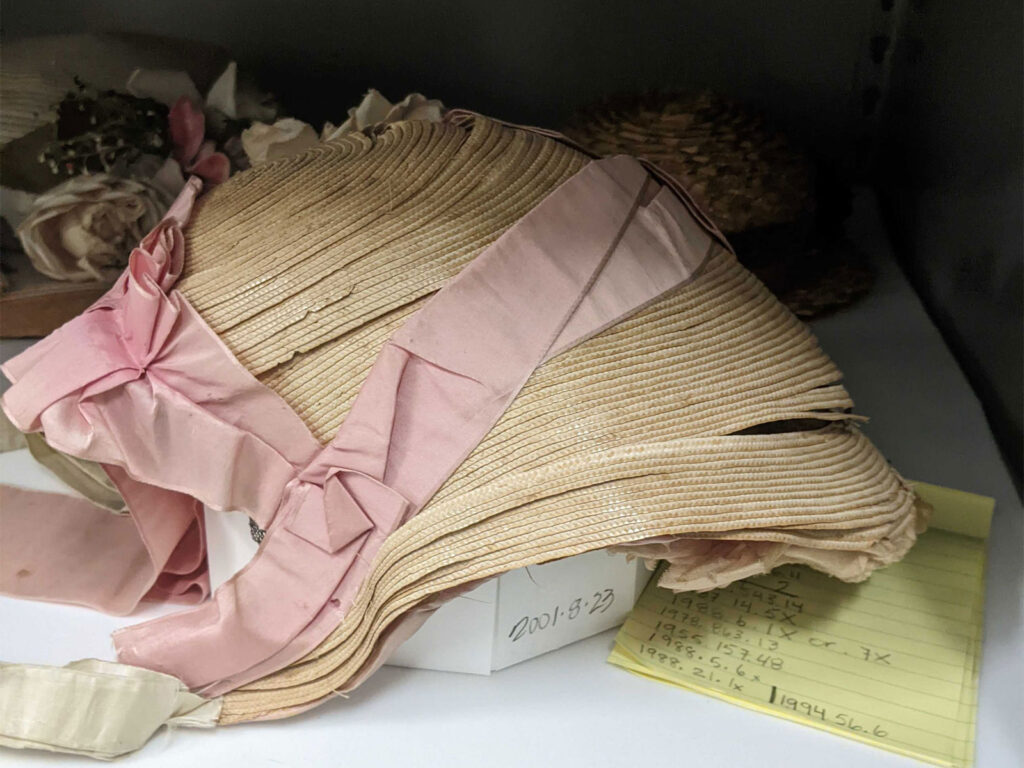

If something has many materials, like a leather-bound scrapbook, we choose unbuffered (our rule of thumb is “when in doubt, leave it out”). The bonnet pictured below is an example of something that needs new housing. The natural straw material is starting to break apart under its own weight, and the silk ribbon is shattering with age. Our care strategy for this object will be to create a cradle lined with unbuffered tissue to fully support the object while also preventing alkaline damage to the naturally acidic silk ribbons.

Water, water everywhere

Unfortunately, I need to start with some jargon for this one: Hygroscopic means materials that absorb water and hydrophobic means materials that repel water. If you know how damaging water can be, you may wonder why we would ever use materials that absorb it. The answer is the Olympic Peninsula!

Our collections building is on a peninsula (that’s on a bigger peninsula) surrounded by water, and we live in a pretty rainy area. This means much of the year we have high relative humidity. A hygroscopic (water-absorbing) material will slowly add or release water into the air, balancing out with the air around it. These materials will change slowly and should be used for items like ivory and paper that are easily shocked with rapid relative humidity changes.

A hydrophobic (water-repelling) material can potentially create a mini-greenhouse effect around an artifact and is usually an inert plastic in museum housing. Because our geography poses the risk of trapping too much moisture inside these items, we use them sparingly. When we do, it’s typically in specific rooms of our collections building or with materials like our decrepit old maps that need to be handled often and/or with extreme care.

Support this year’s priorities!

If you made it this far, you are likely a diehard materials fan and I won’t leave you hanging! Here is what we are ordering for the coming year…

- Unbuffered folder stock for housing our blueprint collection

- New storage boxes for our glass plate collection, which has needed a little TLC

- A few textile boxes for some 50- to 150-year-old quilts, clothing, and uniforms

- Polyethylene sheet protectors for an incoming postcard and correspondence collection

- Folders, folders, folders! We process a lot of archival materials each year!

- Large rolls of unbuffered and buffered tissue to be used on almost everything (it’s truly the multitool of collections care)

- An assortment of acid-free, lignin-free, PAT-passed boxes for archives, photographs, books, and objects

- Acid-free, lignin-free “blue board” (sheets of fancy museum-specific cardboard) that we’ll make into custom-sized boxes

- A freezer, which deserves its own post all about integrated pest management (working title: How Do We Keep Bugs out of Old Stuff?)

All said, collections work is constant, painstaking, and vital…but not cheap. Our community plays an important role in not only contributing items to our collection, but also helping us preserve and protect its contents for years to come. That’s why we’re invite you to show your love for collections care this August!

We hope you’ll consider making a summer gift to support the integrity and longevity of JCHS collections. Gifts of every size have an impact and help us toward our $5,000 goal.